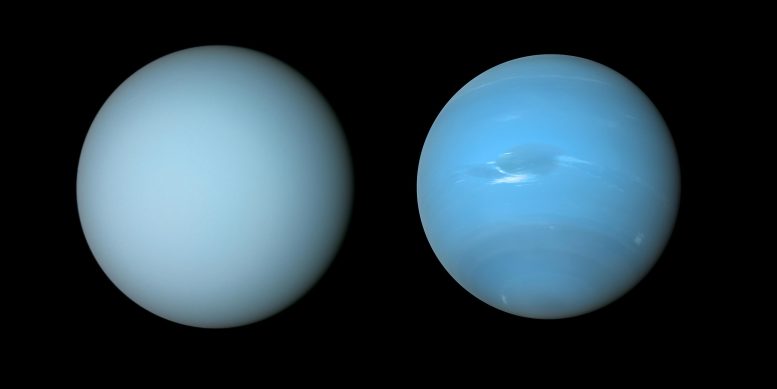

Το διαστημόπλοιο Voyager 2 της NASA κατέγραψε αυτές τις όψεις του Ουρανού (αριστερά) και του Ποσειδώνα (δεξιά) κατά τη διάρκεια πλανητικών πτήσεων τη δεκαετία του 1980. Πίστωση: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

Οι παρατηρήσεις από το Αστεροσκοπείο Gemini και άλλα τηλεσκόπια αποκαλύπτουν υπερβολική ομίχλη[{” attribute=””>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

Οι πλανήτες Ποσειδώνας και Ουρανός μοιράζονται πολλά κοινά – έχουν παρόμοιες μάζες, μεγέθη και ατμοσφαιρικές συνθέσεις – ωστόσο η εμφάνισή τους είναι αισθητά διαφορετική. Σε ορατά μήκη κύματος, ο Ποσειδώνας είναι ορατά πιο μπλε στο χρώμα ενώ ο Ουρανός είναι μια πιο χλωμή απόχρωση του κυανού. Οι αστρονόμοι έχουν τώρα μια εξήγηση για το γιατί οι δύο πλανήτες είναι τόσο διαφορετικοί στο χρώμα.

Νέα έρευνα δείχνει ότι το στρώμα της συμπυκνωμένης ομίχλης που βρέθηκε και στους δύο πλανήτες είναι παχύτερο στον Ουρανό από ένα παρόμοιο στρώμα στον Ποσειδώνα και «λευκαίνει» την εμφάνιση του Ουρανού περισσότερο από ό,τι στον Ποσειδώνα.[1] Αν δεν υπάρχει ομίχλη ατμόσφαιρα Από τον Ποσειδώνα και τον Ουρανό, θα φαίνονται και οι δύο περίπου ίσοι με μπλε χρώμα.[2]

Αυτό το συμπέρασμα προκύπτει από ένα μοντέλο[3] ότι μια διεθνής ομάδα με επικεφαλής τον Patrick Irwin, καθηγητή πλανητικής φυσικής στο Πανεπιστήμιο της Οξφόρδης, έχει αναπτύξει για να περιγράψει τα στρώματα αερολύματος στις ατμόσφαιρες του Ποσειδώνα και του Ουρανού.[4] Προηγούμενες έρευνες για την ανώτερη ατμόσφαιρα αυτών των πλανητών επικεντρώθηκαν στην εμφάνιση της ατμόσφαιρας μόνο σε συγκεκριμένα μήκη κύματος. Ωστόσο, αυτό το νέο μοντέλο, το οποίο αποτελείται από πολλαπλά ατμοσφαιρικά στρώματα, ταιριάζει με παρατηρήσεις και από τους δύο πλανήτες σε ένα ευρύ φάσμα μηκών κύματος. Το νέο μοντέλο περιλαμβάνει επίσης ασαφή σωματίδια μέσα σε βαθύτερα στρώματα που προηγουμένως θεωρούνταν ότι περιέχουν μόνο σύννεφα μεθανίου και πάγου υδρόθειου.

Αυτό το διάγραμμα δείχνει τρία στρώματα αερολυμάτων στις ατμόσφαιρες του Ουρανού και του Ποσειδώνα, όπως σχεδιάστηκε από μια ομάδα επιστημόνων με επικεφαλής τον Patrick Irwin. Το υψόμετρο στο γράφημα αντιπροσωπεύει την πίεση πάνω από 10 bar.

Το βαθύτερο στρώμα (στρώμα αερολύματος-1) είναι παχύ και αποτελείται από ένα μείγμα πάγου υδρόθειου και σωματιδίων από την αλληλεπίδραση των πλανητικών ατμοσφαιρών με το ηλιακό φως.

Το κύριο στρώμα που επηρεάζει τα χρώματα είναι το μεσαίο στρώμα, το οποίο είναι ένα στρώμα σωματιδίων ομίχλης (στο χαρτί αναφέρεται ως στρώμα αερολύματος-2) το οποίο είναι παχύτερο στον Ουρανό από ότι στον Ποσειδώνα. Η ομάδα υποπτεύεται ότι και στους δύο πλανήτες, ο πάγος μεθανίου συμπυκνώνεται στα σωματίδια αυτού του στρώματος, τραβώντας τα σωματίδια βαθύτερα στην ατμόσφαιρα καθώς πέφτουν τα χιόνια μεθανίου. Επειδή η ατμόσφαιρα του Ποσειδώνα είναι πιο ενεργή και ταραχώδης από αυτή του Ουρανού, η ομάδα πιστεύει ότι η ατμόσφαιρα του Ποσειδώνα είναι πιο αποτελεσματική στο να μεταφέρει σωματίδια μεθανίου στο στρώμα της ομίχλης και να παράγει αυτό το χιόνι. Αυτό αφαιρεί περισσότερη ομίχλη και διατηρεί το στρώμα ομίχλης του Ποσειδώνα πιο λεπτό από ό,τι στον Ουρανό, πράγμα που σημαίνει ότι το μπλε του Ποσειδώνα φαίνεται να είναι πιο δυνατό.

Πάνω από τα δύο στρώματα υπάρχει ένα εκτεταμένο στρώμα ομίχλης (στρώμα αερολύματος 3) παρόμοιο με το στρώμα κάτω αλλά πιο εύθραυστο. Στον Ποσειδώνα, μεγάλα σωματίδια πάγου μεθανίου σχηματίζονται επίσης πάνω από αυτό το στρώμα.

Πιστώσεις: Gemini International Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

«Αυτό είναι το πρώτο μοντέλο που προσαρμόζει συγχρόνως τις παρατηρήσεις του ανακλώμενου ηλιακού φωτός από το υπεριώδες έως το σχεδόν υπέρυθρο», εξήγησε ο Irwin, επικεφαλής συγγραφέας μιας ερευνητικής εργασίας που παρουσιάζει αυτό το εύρημα στο Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. «Είναι επίσης ο πρώτος που εξήγησε τη διαφορά στο ορατό χρώμα μεταξύ του Ουρανού και του Ποσειδώνα».

Το μοντέλο της ομάδας αποτελείται από τρία στρώματα αερολυμάτων σε διαφορετικά υψόμετρα.[5] Το κύριο στρώμα που επηρεάζει τα χρώματα είναι το μεσαίο στρώμα, το οποίο είναι ένα στρώμα σωματιδίων ομίχλης (στο χαρτί αναφέρεται ως στρώμα αερολύματος-2) που είναι πιο παχύ πάνω από το Ουρανός Απο Ποσειδώνας. Η ομάδα υποπτεύεται ότι και στους δύο πλανήτες, ο πάγος μεθανίου συμπυκνώνεται στα σωματίδια αυτού του στρώματος, τραβώντας τα σωματίδια βαθύτερα στην ατμόσφαιρα καθώς πέφτουν τα χιόνια μεθανίου. Επειδή η ατμόσφαιρα του Ποσειδώνα είναι πιο ενεργή και ταραχώδης από αυτή του Ουρανού, η ομάδα πιστεύει ότι η ατμόσφαιρα του Ποσειδώνα είναι πιο αποτελεσματική στο να μεταφέρει σωματίδια μεθανίου στο στρώμα της ομίχλης και να παράγει αυτό το χιόνι. Αυτό αφαιρεί περισσότερη ομίχλη και διατηρεί το στρώμα ομίχλης του Ποσειδώνα πιο λεπτό από ό,τι στον Ουρανό, πράγμα που σημαίνει ότι το μπλε του Ποσειδώνα φαίνεται να είναι πιο δυνατό.

Mike Wong, αστρονόμος στο[{” attribute=””>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.

“Ερασιτέχνης διοργανωτής. Εξαιρετικά ταπεινός web maven. Ειδικός κοινωνικών μέσων Wannabe. Δημιουργός. Thinker.”